We've all seen the classic whodunit stories where every character remains a suspect until the very end, at which point a detective finally puts the pieces together to solve the mystery.

Today, scientists across the globe are grappling with a real and very serious mystery: Where are the weak links in SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, and how can science exploit those vulnerabilities to destroy it?

All of the 29 proteins comprising the SARS-CoV-2 are suspects — suspected as possible candidates for drug targets. So is all the RNA genome that the virus uses to build these proteins in its host cell as it seeks to replicate itself.

The SARS-CoV-2 genetic information rests in about 30,000 RNA fragments called nucleotides. That's a lot of suspects. A mystery of that scale and gravity needs more than a detective: It needs a whole army of them.

Luckily, such an army exists. Called the COVID19-NMR project, it is made up of dozens of scientists from around the world using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) high-field magnets to deconstruct SARS-CoV-2. Lucio Frydman, chief scientist for chemistry and biology at the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory and a professor of chemistry at Israel's Weizmann Institute of Science, is one of them. But being a COVID detective is the last thing that Frydman expected to be doing.

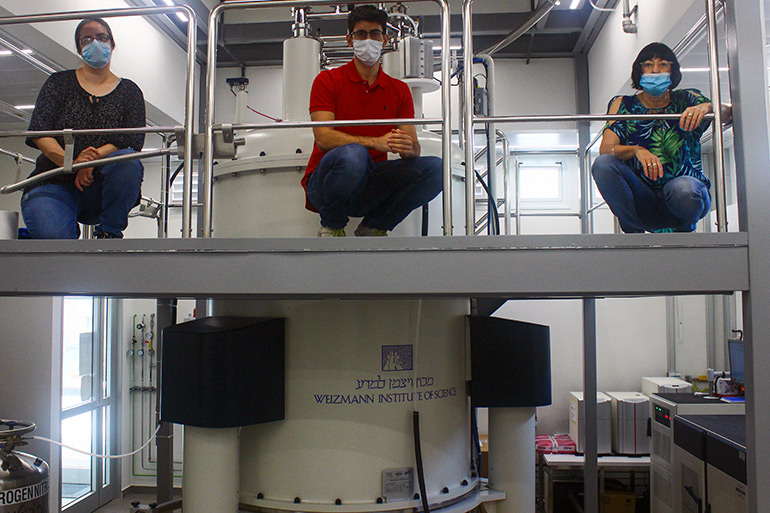

Working on Frydman’s COVID research are Weizmann Institute scientists Sabine Akabayov (left) and Tali Scherf (right), and Ph.D. student Mihajlo Novakovic (middle).

Photo credit: Rahamim Guliamov

"If you had told me six months ago that I'd be running NMR spectra on viral RNAs, I would have laughed," he said recently from his office outside Tel Aviv, "because it was really very far away from our activities and our interests."

But Frydman, an international expert in NMR technique development, got "very annoyed" when the pandemic sidelined him and began looking for ways to make himself useful. When he heard about the NMR project, he knew he had something to contribute.

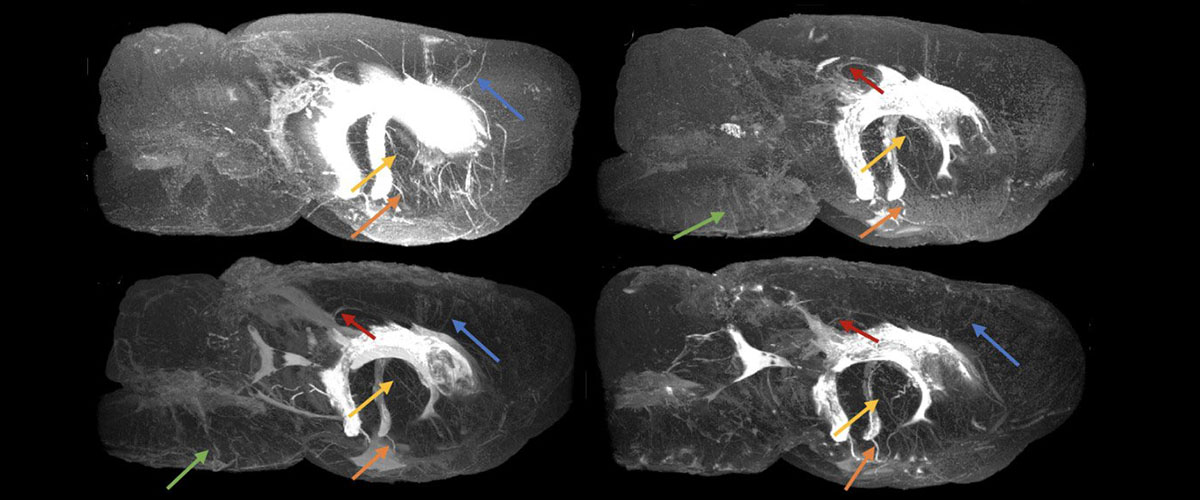

Headquartered at Goethe University in Frankfurt, Germany, the project's mission is to use NMR to examine the proteins and RNA fragments that make up the virus. NMR uses magnets and radio waves to find out how atoms that make up these structures are connected, and how those relationships define their dynamic function. By monitoring SARS-CoV-2 constituents in their native environment, this technique, which yields amazing detail when coupled with high magnetic fields, could help scientists identify Achilles’ heels in those structures vulnerable to the right drug.

Given the high stakes, this is definitely not science as usual. The teams are working quickly and openly sharing results as they resolve one protein and RNA fragment after another. Frydman's team is already drafting their first publication.