Read updates from MagLab faculty researcher Lydia Babcock-Adams as she journeys aboard the Research Vessel Roger Revelle on a National Science Foundation expedition to Antarctica.

The science is officially over! We are currently in the Drake Passage, making our way back north. The weather in the Drake is much calmer for this crossing – it is a gorgeous, sunny day! We are busy packing, inventorying, and cleaning so that when we arrive at the dock we can start offloading everything. There is a lot to be done after almost 50 days at sea!

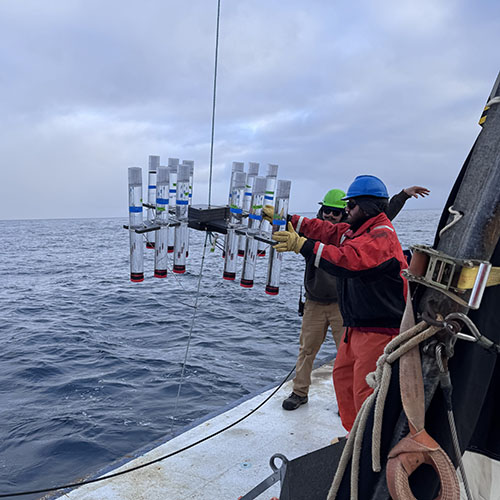

Lydia Babcock-Adams working with a sediment trap aboard the Research Vessel Roger Revelle. Scientists working on the deck of the boat must wear float coats and hardhats for safety.

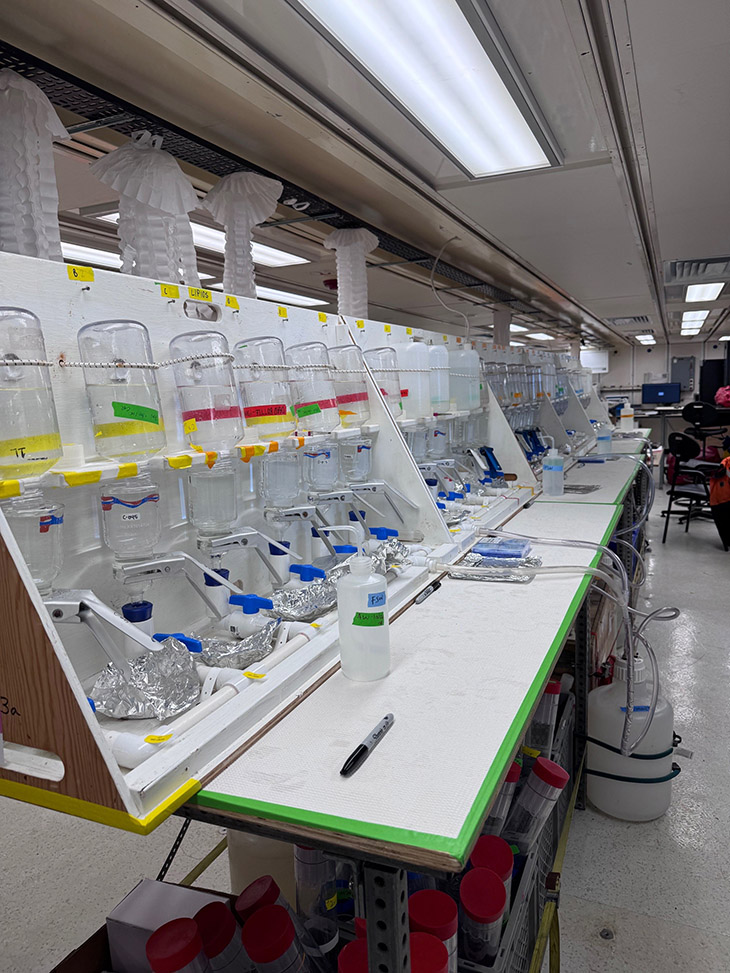

While we are transiting, I want to tell you more about some sampling we did at the process stations. Remember, those are the stations where we stayed in the same spot for a few days to do experiments. The experiment that the group I’m working with did at process stations is called a sediment trap to look at the characteristics of the organic material that is sinking from the surface down deeper into the ocean. These kinds of experiments tell us what types and how much carbon is making it into the deep ocean rather than getting recycled at the surface. We deploy a long line with a weight at the bottom and at certain depths we attach a cross with twelve tubes. Each tube has two layers. On the bottom is a brine solution with a little bit of formaldehyde. The brine (just salt added to filtered seawater) is denser than the surrounding seawater, so it stays on the bottom of the tube, and the formaldehyde is to preserve particles as they fall into the tube. The layer above this is filtered seawater, which is just to fill up the tube so that it is full when it goes into the ocean.

Scientists and crew deploy a sediment trap and the accompanying floats aboard the Research Vessel Roger Revelle.

Once deployed, the traps float around on their own for 24 hours. We have a GPS tracker attached to them so that we can keep an eye on where they are going (if they were to drift into shallow waters we would need to go over and pick them up). When it’s time to pick them up, we steam to the latest GPS location and use binoculars to spot the yellow floats. Once we have eyes on a float, the captain (or one of the mates) brings the ship up so that the trap is along the starboard (right) side. We use a grappling hook to grab the line that the floats are attached to and then bring it around to the back of the ship to bring everything back on board.

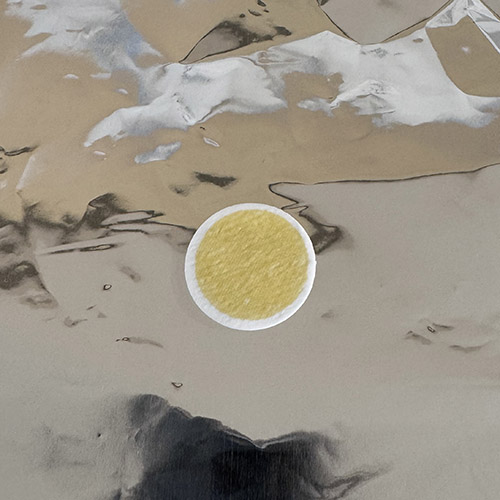

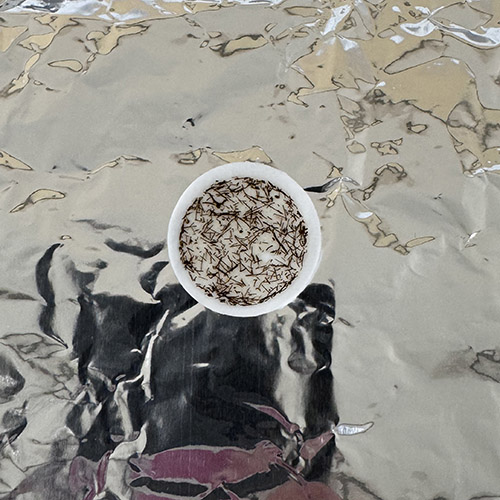

Once we have retrieved all the tubes, the filtering begins! Like the other samples we’ve been taking, we pass the water over filters and collect what is caught by the filter.

Two filters used on seawater collected aboard the RV Roger Revelle. On the left, the green is from phytoplankton in surface seawater. On the right, the thin brown lines are krill poop.

Processing the sediment trap samples is a lot of fun because we often see some zooplankton and a ton of krill poop. Krill are a super important piece of the food web here because that’s what penguins and whales eat.

Until the next watch,

Lydia

A Day in the Life

You may be wondering, “what does a typical day at sea look like?” – well here’s your answer! I made note of the time during my first night shift, sampling along the 200 line.

| 23:00 |

My alarm chimes – it’s time to get up! I know I’ll be outside to sample water a few times today, so I put on a warm base layer. When I come up from my bunk I immediately throw on my winter coat and go outside to see the beautiful full moon. I haven’t seen it since we were in port in Punta Arenas since I’ve been on the noon to midnight shift until now!

The full moon from aboard the RV Roger Revelle. |

| 23:28 | I head up to the galley to grab some coffee and breakfast. There are bagels, so I toast one and slather on cream cheese. As we are up at all hours of the day and night, there is always a pot of coffee on the heater. The rule is that if there is one cup or less left in the pot you brew a fresh pot. Nothing worse than waking up and not having coffee ready! |

| 23:50 | We are at a station (200.040; this station is 40 km from the coast on the 200 line), so I grab a seawater sample from the underway tap in the lab – if you remember from my previous post, this is the “seawater on demand” system that I’ve been collecting my samples from that will get analyzed with the MagLab’s 21 T FT-ICR mass spectrometer to look at the dissolved organic compounds. |

| 00:00 | The official start of my shift! We check in with the day shift crew for information on how their shift went and we take over filtering the samples from the underway station (200.060; now we’re 60 km from the coast) |

| 00:31 | We just finished filtering and make sure that we’re all set up for sampling at the next underway station, 200.080. We’re about ten minutes away! |

| 00:40 |

We head over to the hydrolab where the underway sampling is happening, then bring everything back to the main lab to process. While the samples are filtering I move the supplies we’re soaking in an acid bath into a water bath to rinse. We clean our sampling equipment in between stations to make sure there is no cross-contamination. We prepare all our sampling supplies for the next station which is a fille CTD rosette cast to the bottom.

At the start of my shift I turn the page on my Wheel of Fortune calendar. It helps me keep track of what day it is, and it’s fun! |

| 01:26 | All done with the samples from 200.080 and ready for 200.100! |

| 01:39 | We arrive on station and send the CTD rosette down to the bottom, 428 meters (1404 feet) deep here.

HOW THE GRID WORKS:The research grid is comprised of parallel lines, 100 km apart (~62 miles) extending offshore from the coast of the Western Antarctic Peninsula, each line about 200 km (~124 miles) long. Along each grid line there are stations 10 km apart where the research vessel collects seawater samples.

The Palmer Long-Term Ecological Research study area, “the grid.” (Palmer Station LTER.) |

| 01:45 | I grab a seawater sample from the underway system for my analysis of dissolved organic compounds. |

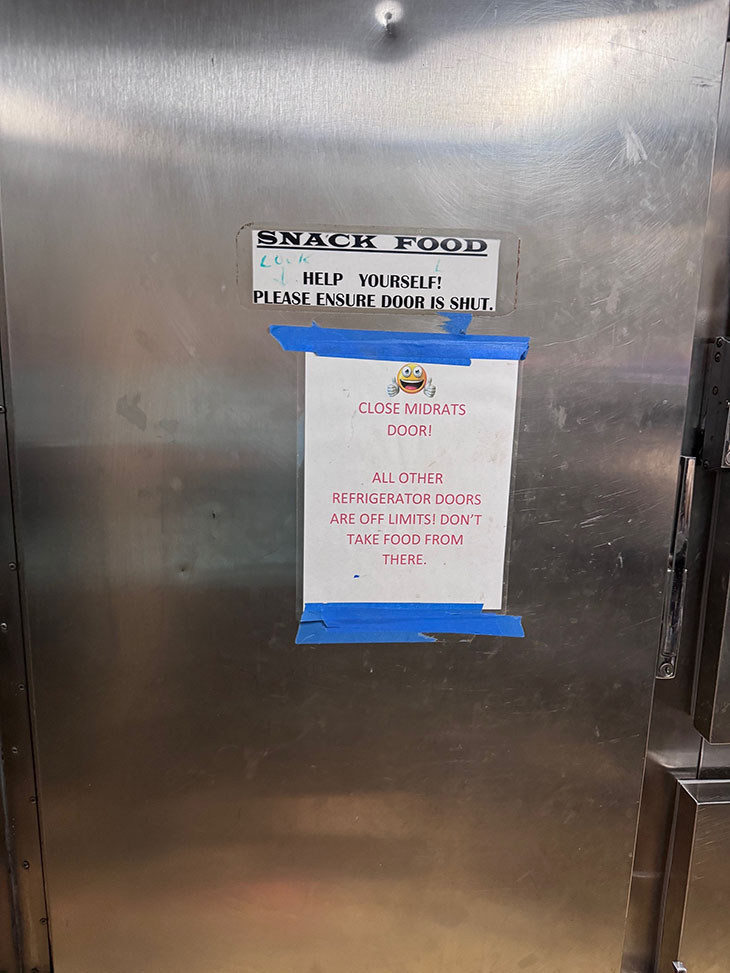

| 01:55 | I’m hungry, so I head up to the galley for a mac & cheese snack before we sample the CTD rosette. There is the midrats fridge, which has leftovers from meals that we’re allowed to eat whenever. Midrats stands for “midnight rations.”

The midnight rations, or “midrat” fridge of leftover meals for overnight snacks. |

| 02:03 | I check in to see where the CTD rosette is – we are almost at the bottom! |

| 02:20 | I suit up in all my waterproof gear and carry sampling supplies out to the CTD rosette bay. |

| 02:29 | The CTD is on deck! Let the sampling begin. |

| 03:39 | After more than an hour, we’re all done sampling, now to begin processing and filtering. |

| 04:47 | We’ve finished processing and have reset everything so that we are ready for the next station, which is an underway station. |

| 04:53 | I’m a little hungry again, so I’m back up in the galley for a cereal snack – Apple Jacks for me today! |

| 05:43 | We head to the hydro lab to get the underway samples and begin the processing. |

| 06:34 | All done! We’ve got about 10 minutes until the next underway station – I’m going to try to get some emails done. |

| 06:50 | We grab the underway sample and start processing. |

| 07:35 | Luckily, we finish just in time to go to our first hot meal of the day – breakfast. |

| 08:48 | We collect the last underway samples of this line! The next station is a CTD rosette station. |

| 09:34 | All done processing those samples and ready for the next station. |

| 09:46 | We are on station and the CTD rosette is in the water! The seafloor is 3,647 meters (11965 feet or 2.2 miles) here, so it will take a while to reach the bottom. A nice break for us! |

| 11:05 | We finally made it to the bottom! Now as we bring the CTD rosette up through the water we will close bottles at the depths where we want to take samples. |

| 11:30 | Lunch time while the CTD rosette is on the way up. |

| 12:00 | And just like that, my shift is over! The CTD rosette isn’t quite up yet, but the day shift crew will take care of those samples. I relax and wind down a bit before heading to bed. |

| 13:24 | Time to get some sleep, it will be another busy shift tomorrow sampling along line 100! |

Until the next watch,

Lydia

We are officially in the thick of our sampling! The Palmer Long-Term Ecological Research (LTER) project began sampling along the West Antarctic Peninsula (WAP) over three decades ago. Since then, scientists have come back year after year to sample at the same locations to track how the ecosystem is responding to climate change – the polar ecosystems are among the most rapidly changing on Earth.

The grid, as it’s called, is comprised of parallel lines, 100 km apart (~62 miles) extending from the coast to offshore, each line about 200 km (~124 miles) long. Along each grid line we have two types of station. One is an underway station where we collect just surface seawater using the underway seawater system on the ship which pumps seawater through a series of pipes into a couple of sinks in the labs.

The other is a CTD station where we collect seawater samples from the surface of the ocean all the way down to the bottom using what’s called a CTD rosette.

From NOAA Ocean Exploration: “CTD stands for conductivity, temperature, and depth, and refers to a package of electronic devices used to detect how the conductivity and temperature of water changes relative to depth. The CTD is an essential tool used in all disciplines of oceanography, providing important information about physical, chemical, and even biological properties of the water column. On exploration vessels, a CTD is often attached to a larger metal water sampling array known as a rosette that is lowered into the water via a cable. Multiple water sampling, or Niskin, bottles are often attached to the rosette as well. These bottles are open when the rosette is deployed and can be triggered to close, collecting water samples at specific depths for later analysis.”

The CTD rosette is made up of a carousel of bottles with some sensors attached. It gets lowered into the ocean using a winch with a very long cable. Before sending the package down, we open all the bottles at the top and bottom so that as it moves down through the water the bottles get rinsed out with seawater. While the CTD rosette makes its way down to the bottom of the ocean, the sensors are sending data back to a computer lab on the ship where we gather to decide what depths we want to collect water from. This data includes salinity (how salty the water is), temperature, dissolved oxygen, and fluorescence (how much chlorophyll is in the water).

Once we have decided on the depths and the CTD rosette has reached the bottom, we slowly bring it back up, pausing at each depth to close bottles, trapping the seawater inside. Once the CTD rosette is back on deck, it’s go-time for the scientists! We wait with our sampling supplies in hand as the CTD rosette rolls from the ship deck into a semi-enclosed bay where we do the sampling.

The team I’m working with collects samples to measure seven different parameters, some that we collect as “whole water”, which means right off the bottle, some that we collect as filtered water, which means we remove any particulate material, and some that we collect as whole water off the bottle then bring into our shipboard lab where we filter it and save what gets caught by the filter. The entire process from when the CTD rosette gets wheeled into the sampling bay to when the last sample is done filtering is typically about two and a half hours.

Water samples in a lab aboard the ship.

Since we are a team of four, we split into two shifts, noon to midnight and midnight to noon. So far, I’ve been on the noon to midnight shift, but we will be swapping shifts soon. Other than when the meals are served, it doesn’t really matter when you’re awake down here since it’s close to 24-hours of daylight!

Until the next watch,

Lydia

It’s been a busy week; I have so much to update you on! From where we left off –

We exited the Strait of Magellan on January 11 and made our way south along the coast of Tierra del Fuego, Argentina, towards the Drake Passage. It was very calm in the Strait, but the seas picked up as soon as we entered the Atlantic Ocean. When crossing the Drake, you hope to have what people call “the Drake Lake”, which means calm seas. However, the Drake is well known for tough crossings with high winds and big swells – that crossing is called “the Drake Shake”. The first day of our crossing was closer to a Drake Shake I’d say. We had winds over 40 knots (1 knots = 1 nautical mile per hour) and the swells were up to 15 feet. Luckily, my sea sickness medicine kept me feeling okay during this bad weather, so I was able to look out the port holes and see the waves crashing over the back deck. During bad weather like this, the captain secures the decks which means we aren’t allowed to go outside. Lucky for us, the bad weather only lasted a little more than 24 hours and we had calmer seas for the rest of our crossing.

During the crossing we were deploying instruments called XBTs, or Expendable Bathythermographs. To deploy these, we load a tube with the instrument inside into the launcher and then drop the instrument overboard. It’s got a long copper wire which transmits the temperature back to the computer. The depth of each temperature measurement is calculated based on how fast we know the instrument falls through the water. We deployed an XBT each hour through the Drake (as weather permitted) with two scientists taking a 6-hour shift. You can see a photo of me on the back deck holding the launcher while the XBT falls through the water and my lab mate, Danny, watching the temperature plot on the computer screen.

Finally, early on the 15th, four days after leaving the Strait of Magellan, we arrived at the U.S. Research Base, Palmer Station. The Noosfera, a Ukrainian research vessel, was docked at the station, so we stayed offshore and used small boats to transport some people and supplies to and from station.

We also used this time as an opportunity to do some safety training on small boat operations. There will be some science happening from small boats, so we all learned what supplies to bring with us, how to go down the ladder to the small boat, and how to get back up! We took a boat ride around the area and got to see several humpback whales, a penguin colony, and icebergs which was so cool. After all the transfers were complete, we headed off to our first official station to collect water samples.

More next time on how we collect seawater samples and what we do with them after that!

Until the next watch,

Lydia

Greetings from Punta Arenas, Chile!

My travels began almost a week ago, on Saturday January 3 out of Tallahassee. It was a long journey to Chile involving a four and a half hour delay in the Atlanta airport, and rogue luggage that went through Miami to Santiago, rather than on the plane with me from Atlanta to Santiago.

Finally after about 36 hours of travel I made it to Punta Arenas, on the southern tip of Chile. Although it was 11:30pm when we stumbled out of the airport, it was still twilight because of how far south we are here. This time of year, summer in the southern hemisphere, the sun rises around 5:30am and sets around 10pm – that’s 16 and a half hours of sunlight! It’s convenient for all the work we’ve been doing loading science gear onto our ship, but it has totally messed with my internal clock.

Mobilization began on January 5 which included loading all the science gear on the ship. They have lab spaces for us which include benches, drawers, cabinets, fume hoods (for working with solvents or acids), and chemical storage, but we bring all of our science supplies. We’ll load the last bit of cargo on the ship tonight and then head out through the Strait of Magellan early tomorrow morning. This strait is an important passage between the Pacific and Atlantic oceans; however, it is very difficult to navigate because it can be quite narrow in spots and there are often high winds and fast currents. We will have a pilot coming onboard tonight who will safely navigate us through the passage, then he will get off the ship before we head south towards Antarctica.

In addition to setting up the labs, we are also having meetings about safety. We all need to know how to respond in the event of an emergency. On the ship we have an alarm. The pattern of the alarm alerts us as to what the emergency is. If it’s three short blasts that means there is a fire or piracy (though we aren’t too concerned about piracy in this part of the world). If it’s seven short blasts followed by a long blast that means man overboard. If it’s one long blast it means abandon ship.

We are also each assigned a life jacket and a survival suit which we may need depending on the emergency. Although going through the safety training is serious because there are real dangers here, it is always fun when everyone is trying on the survival suits. They will keep us warm and floating in the water but are cumbersome on land! We are also assigned extreme cold weather gear from the US Antarctic Program, which includes boots, lots of different types of gloves, hats, and various pants and jackets that we may want for operations out on the deck. Although it is summer down here it is still cold!

While I’m at sea I’ll be posting as often as I can about the science conducted on the ship as well as what it’s like to live on board.

If you have any specific questions, contact me at babcock-adams@magnet.fsu.edu and I will respond as I can. We have internet on the ship, but it is limited (and the farther south we go the spottier the coverage may be).

Until next time,

Lydia

R/V Roger Revelle is operated by Scripps Institution of Oceanography under a charter agreement with the Office of Naval Research. Roger Revelle is one of six major oceanographic research vessels owned by the U.S. Navy and operated for shared-use through the University-National Oceanographic Laboratory System.

The National Science Foundation is the primary U.S federal agency supporting research at the frontiers of knowledge, across all fields of science and engineering (S&E) and all levels of S&E education. Important support for research vessel operations at Scripps Institution of Oceanography is supported by the National Science Foundation (including awards 1119644, 1212770, 1227624, and 1321002).

Last modified on 25 February 2026