Komalavalli Thirunavukkuarasu had been a postdoctoral researcher at the National MagLab for more than a year before she finally found someone she could talk to.

It's not that her supervisor wasn't available, or that her husband, also a physicist, ignored her when she came home after a long day.

But she was missing someone at work to bounce ideas off of, seek advice from. Someone about her age, at approximately the same point in her career, who understood where she was coming from, was a good listener and could give her straight but sympathetic feedback.

In a word, she needed a peer mentor (well, OK, two words) — although when she finally fell in with a group of fellow postdocs, that's not how they thought of each other. "We have never labeled it as peer mentorship," said Thirunavukkuarasu, now a visiting associate in research in the lab's DC Field Facility and assistant professor at Florida A&M University, "but we have always been doing that."

In peer mentorship, someone who has lived through an experience provides guidance and support to someone who is new to it. Used widely in education and the workplace, peer mentoring programs typically pair "mentees" with someone just slightly older (and presumably wiser) who can help a mentee with everything from a "dumb" question to a mini crisis. The arrangement allows both parties to develop technical as well as "soft" skills in the context of a relationship that's part professional, part personal.

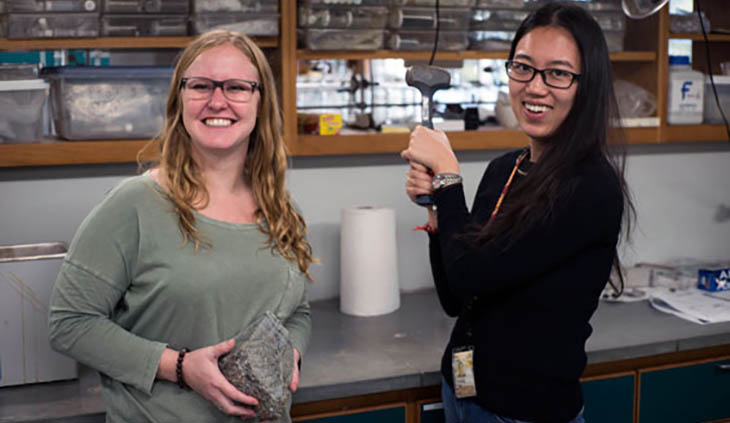

Shuying Yang (right) has been a peer mentor to fellow geochemistry graduate research assistant Stevie Henrick.

MagLab graduate student Stevie Henrick has relied on a small group of peers in the Geochemistry Group for the past few years. "I never considered what we did mentoring," she said. "It was just kind of this circle where we all help each other out."

Whatever you call it, it plays a big role in shaping scientists.

Help from people who aren't your boss

Supervisors play a critical role in training young scientists, but they can't meet every pedagogical need. They're busy. They're decades older. And they want their students, for their own good, to figure a lot of stuff out on their own.

Peer mentors come in to plug those little educational holes.

Amelia Estry, a Florida State University physics major and a lab assistant at the MagLab, has learned that the smartest or most experienced scientist may not be the one best able to answer her questions. "A lot if times it's easier for information to kind of trickle down," Estry said, from senior staff to postdoc, from postdoc to grad student and from grad student to undergrad.

Then there are questions you don't want to ask your boss for fear of looking like an idiot.

"I come from a culture where the teacher is almost a god," said Thirunavukkuarasu, who arrived at the MagLab from India by way of Germany. "So for us to offend them or to be judged by them as stupid is something not acceptable."

Talking to a peer isn't as scary. "You're more likely to be nervous around a professor," noted Estry. "But around your friend you can talk freer."

That emotional connection is an important part of the mentoring dynamic, said Kari Roberts, a program coordinator with the MagLab's Center for Integrating Research & Learning. A mentor's best tools are her ears.

"Because you're a peer mentor, you don't have all the answers," said Roberts. "So you have to be able to listen to the other person, really try to understand where they are."

A conversation, not a lecture

Talking to peers is, of course, fundamentally different than talking to a boss — more a conversation than an information download. A mentor doesn't necessarily need to know more than the mentee. In fact, colleagues researching different areas can offer novel points of view, said Thirunavukkuarasu, who met with her German colleagues at daily coffee breaks to discuss each other's work.

"Someone in the group would just come up with some different thought process, and that would just trigger a lot of ideas for myself," she said. "They would just give a different perspective that would clear my mind and help me find my way out."

Fresh perspectives help scientists no matter what their level. David Podgorski, a staff scientist in the lab's Ion Cyclotron Resonance Facility, has conversations with colleagues that often inspire new insights. At biweekly group meetings, ICR Facility Director Chris Hendrickson often solicits ideas and feedback from his team.

"Maybe the question you ask or the idea that you throw out initially isn't the right one," said Podgorski. "But you can take that and start to shape it based on the feedback from others, and then it becomes a good idea or a good question."

In fact, conferring and debating with peers is integral to the scientific process. It can stoke neurons, open new windows in the brain, change not simply what someone is thinking, but, more profoundly, how they're thinking.

"There's no single person who has expertise in everything," said Podgorski, "so it's good to take expertise from x, y and z, and add them together to get a final product."

Mentoring as on-the-job training

Peer mentors develop important job-related skills, such as teaching, counseling, communication and supervising.

Before she became an informal mentor, Thirunavukkuarasu "never opened my mouth," she said. The more she developed as a peer mentor, however, the more she grew into a confident, nuanced communicator — a skill she said any successful scientists needs.

"[Academic] advisors usually take the straight path. They say, ‘This is bull,' or something," said Thirunavukkuarasu. "But when we talk to another postdoc or grad student, we generally cannot do that, and we actually learn the polite way of saying it."

Having to show fellow undergrads how to make crystals or build probes not only helped Estry better understand those tasks herself, but made her more comfortable in the role of a teacher.

"It gave me the chance to consolidate my thoughts," said Estry. "I have a tendency to start rambling when I explain things — I kind of skip around. So it really helped focus my thoughts and explain, ‘OK, this is what we're doing, step by step.' "

Peer mentors also get a taste of what it might be like to supervise other scientists one day. Scientists and academics don't always pick up human relations skills along the way, said Thirunavukkuarasu, so the more experience future advisors and bosses get managing people, the better.

By Kristen Coyne

Photos by Stephen Bilenky