The official business hours of the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory are 8 a.m. to 5 p.m., Monday through Friday.

But the official science hours are 24/7.

Every evening, administrators, technicians and other staff at the MagLab’s three sites head home after a long day in the office, workshop or lab. But because our unique facilities are in such high demand, our magnets are almost always open for business.

So no matter the day of the week, no matter the time of night, there are always scientists running experiments at the lab, as well as MagLab staffers working to support them. At our headquarters in Tallahassee, the last staffer out the door leaves at 3 a.m. The first arrives two hours later.

The MagLab is open 24/7 for science.

"We have many more people applying to use our magnets than we have availability," says National MagLab Director Greg Boebinger. "We offer scientists world-record magnetic fields and some of the best technical support out there, so we do whatever we can to accommodate as many experiments as possible."

At the MagLab, it’s non-stop science.

At most of our seven facilities, "users" (that’s what we call the scientists who travel to the lab from across the world to conduct experiments) can be found hard at work morning, noon and night. Even if they aren’t physically present, they may toil into the wee hours from their home institutions, thanks to technology that allows them to access some magnets remotely.

However, our DC Field Facility, home to the largest number of our magnets, sees the most traffic. The 75,000-square-foot area includes several superconducting magnets that operate continuously. Where the magnets work around the clock, so do the scientists. If you pass by one of those instruments in the wee hours of the morning, says DC Field Facility Director Tim Murphy, "… there is a 98 percent chance you’ll see someone sitting in a chair taking data, trying desperately to stay awake."

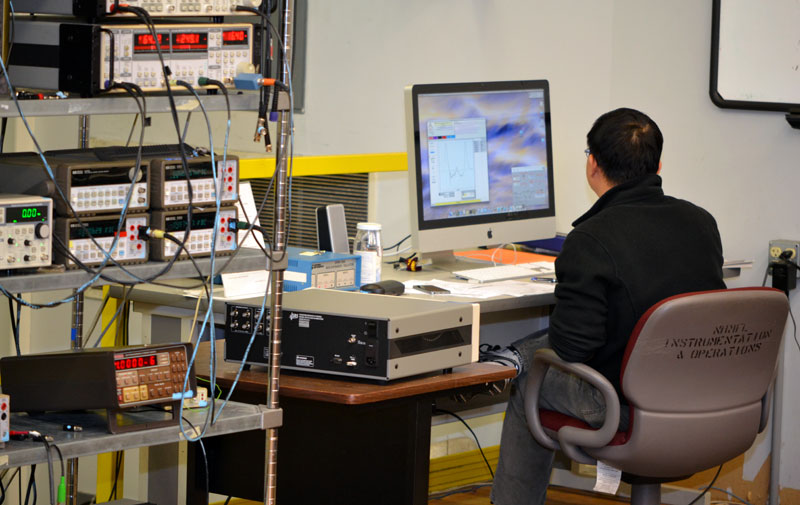

An operator in the DC Field Facility's control room keeps an eye on experiments.

After all, DC Field Facility users have just a week to conduct their experiments. Then it’s time to pack up and make way for the next scientist. So they cram as much work as possible into those few days, laboring toward that holy grail of science, publishable data. Forgoing luxuries like sleep is a small price to pay for such a prize.

Scientist Wei Pan has labored through many a night in the lab's Millikelvin Facility.

Wei Pan, a physicist from Sandia National Laboratory who uses the lab’s superconducting magnets to study the quantum Hall effect, feels the pressure during his visits. Mindful that his experiment was selected over competing proposals, he tries to use his limited time wisely so that he will have something to show for it.

"This is a very unique facility," says Pan. "It’s only one week, you want to get as much data as you can."

Getting "magnet time" at the MagLab is a big deal for scientists. They apply months in advance, describing the planned experiment and arguing why it’s more compelling than competing proposals. If their request is successful, they spend weeks before their arrival preparing their instrumentation and samples.

"It’s a once-a-year kind of thing for many of our users," notes Dan Freeman, part of the team who operates the world-record 45 tesla hybrid magnet. Users don’t want to blow it.

The stakes can seem especially high for users of the 45 tesla x Tesla, or T, is a unit of magnetic field strength; a strong refrigerator magnet is .01 tesla, and a typical MRI machine is 1.5 to 3 tesla , the lab’s most in-demand magnet. Operating this powerhouse, which pairs a superconducting magnet with a resistive magnet, costs $4,000 an hour, most of that in electricity. Although scientists use our magnets for free (thanks to funding from the National Science Foundation and the state of Florida), the pressure is on to produce research worthy of the price tag.

"Running experiments in the hybrid is very tiring," says Murphy. Factor in the jetlag suffered by many far-flung scientists and the fatigue is even greater. "By the end of the week, the users are exhausted. We try to tell first-timers up front, but they usually have to learn the hard way."

Every morning, a hybrid operator reports to work at 5 a.m. to ramp up the magnet – often to find users waiting to start the day’s experiment. Staffers have even had to rouse a scientist sacked out on the floor in a sleeping bag. Although the hybrid stops running at 6 p.m. every evening, researchers are often up late preparing for the next day of magnet time.

Elsewhere in the DC Field Facility, scientists using one of the powerful resistive magnets are also sometimes found slumped over a desk in the dead of night, like a student cramming for a final exam. Users closely monitor experiments from start to finish: Depending on their data, they may want to make on-the-fly adjustments to the temperature, pressure, magnetic field or the sample’s angle within that field.

Resistive magnet users have access to the magnet’s field for nine and a half hours a day, during either the day or night shift. But it’s not unusual for them to spend twice that time in the magnet "cell" -- the 750-square-foot room where the magnet and related electronics, cryogenics and sample prep tables are located – preparing or reviewing data.

The DC Field Facility is a cold, creaky, cavernous place, its pipes rushing with water and busbars buzzing with current. According to control room operator Joseph Petty, making rounds during the lonely late shift is like a mall cop patrolling at midnight. "You have this huge building and empty hallways," says Petty. "You’re hoping you’re not going to find a surprise around the corner."

"Wei Pan monitors data from his experiment in the Millikelvin Facility.

But for user Wei Pan, burning the midnight oil at the lab isn’t creepy -- it’s peaceful and productive. He takes advantage of the solitude by talking to himself about his experiment, which helps to clear his mind.

"It’s better because you’re by yourself and you tend to think deeper," says Pan.

Best, though, is when the hard work, long nights, jetlag and time away from family and job all pay off with exciting data that adds something new to science. That, says Pan, "is like winning the lottery."

By Kristen Coyne