Sports aficionados have a full calendar of must-watch events scheduled throughout the year - the World Series for baseball buffs, the Superbowl for (American) football fans, the Tour de France for cyclists, the Masters for golfers and, every several years, the Olympics and FIFA World Cup.

But beyond the fields, tracks, greens and courts, another kind of teamwork is taking place in laboratories across the globe: science teamwork.

It's more than a feel-good idea: The sciences have become increasingly collaborative over the decades by necessity. It takes bigger teams featuring more co-authors to produce journal articles, and those multidisciplinary papers have a greater impact, said Dr. Allan Brasier, director of the Institute for Translation Sciences at The University of Texas Medical Branch. In fact, studying how scientists work in teams has become its own discipline, called the science of team science (or SciTS), which explores the latest methods and tools used by successful science teams.

While complex, high-stake problems help drive the teamwork trend, you can't just throw a bunch of researchers at a science puzzle and expect eurekas to ensue.

"It's not a forgone conclusion that, when you get a group of people together, they will form a good team," said Brasier, who just chaired the ninth annual SciTS Conference in May.

Fielding a good science lineup, he said, requires consensus, vision, clarity and cohesion. Adopting best practices that promote those things will lead to better results.

Teamwork is ingrained in the day-to-day life of the National MagLab. Without close cooperation among all staffers — from technicians to administrators to grad students to chief scientists — research here just wouldn't happen. So, to celebrate good science teamwork, we recruited a few "good sports" across the lab to suit up in uniforms from local athletic teams. Then we photographed them with our world-record magnets and spoke with a few to learn more about how good teamwork makes good science. (You can help promote team science by printing out and pinning up the poster versions of these photos at the end of this story).

Teams drive innovation

Representing the Magnet Science & Technology team, building a magnet coil, are (from left to right): technician Jim O'Reilly, webmaster M Tabtimtong, technician Randy Helms, chief scientist Laura Greene and technician Brent Jarvis.

National MagLab Chief Scientist Laura Greene's distinguished career in physics has coincided with the steady rise of teamwork in her field. Early on, she worked mostly on her own.

"That's sort of how I was raised as an undergrad and grad student," said Greene (pictured above), past president of the American Physical Society and a member of the National Academy of Sciences. "They wanted to see that you could do your own work."

But she got a crash course in teamwork when she landed at Bell Labs, especially after high-temperature superconductors were discovered in 1987. Scientists who wanted to experiment with the new materials needed to team up with those who grew them. Collaborations sprouted everywhere, Greene said, and they made the physics better.

"It was impossible not to do teamwork," she said of the heady era. "All of a sudden papers that would have had two, three of four authors would have 15."

In the years that followed that trend continued: superconductor experts teaming up with semiconductor gurus, theorists partnering with experimentalists, physicists joining forces with chemists.

"To tackle problems that are really complex," Greene said, "you need to come to it from different perspectives."

Making a place for teams

Representing the Nuclear Magnetic Resonance team, standing in front of the world-record 900 MHz NMR Magnet, are (from left to right): MagLab Director Greg Boebinger, Public Affairs intern Abigail Engleman, Safety Engineer Alfie Brown, NMR graduate research assistant Ghoncheh Amouzandeh and NMR physical chemist Frederic Mentink-Vigier.

When physical chemist Frederic Mentink-Vigier (pictured above) does science, he's gotta talk it out.

"When I'm doing theoretical models, I need someone, or a few people, to discuss it with," said Mentink-Vigier, a visiting research faculty member who is developing dynamic nuclear polarization techniques in the MagLab's NMR-MRI Facility. "That's actually the way I can shape ideas, make sure of the directions I'm thinking and whether they are relevant or not."

It's important to find sounding boards outside your own area of expertise, Mentink-Vigier said. And it's important for scientists to have natural meeting points where science serendipities can happen. To paraphrase a well-worn sports film quote, if you build a break room, they will come.

"You need a place where people can meet and discuss randomly, a space where they can really have free discussions," he said. "It looks like a waste of time when people are taking a coffee, but it's actually a very efficient way of having information flow."

Team goal #1: Don’t kill each other

Representing the DC Field Facility team, standing in front of the world-record 45-tesla hybrid magnet, are (from left to right): physicists Audrey Grockowiak, Stan Tozer, Hongwoo Baek, William Coniglio and Jonathan Billings.

MagLab physicist Audrey Grockowiak (pictured above) often teams up with colleagues Stan Tozer and William Coniglio (all pictured above) on experiments that subject materials to high magnetic fields and high pressures, using little pressure cells of Tozer's design. Materials do strange things under high pressure. So do people.

Despite (or perhaps because of) having collaborated closely for years, the three researchers have been known to lose patience with one another.

"We go together on long trips, we are tired, we will make mistakes," said Grockowiak. "At some point we'll want to kill each other or slap each other or punch each other."

So in addition to communication, hard work and passion, Grockowiak said, teamwork requires tolerance and forgiveness. After all, she said, they’re not just scientists: "We're humans."

Forgiving the occasional misjudgment is easier when science teams have built up a solid foundation of trust.

"There has to be [trust] for these kind of experiments," Grockowiak said. "We depend on each other."

Putting the science first

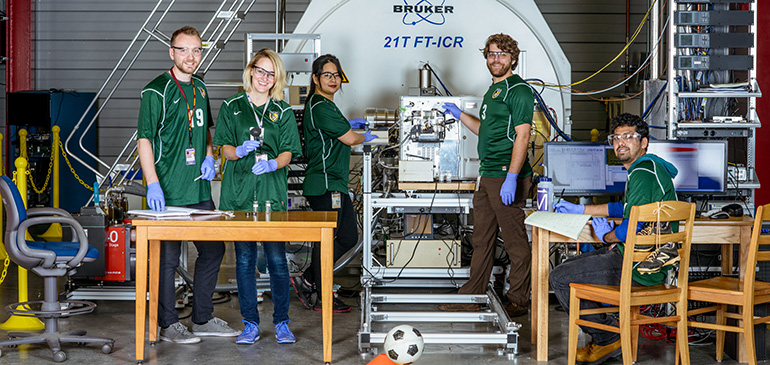

Representing the Ion Cyclotron Resonance team are (from left to right): Matthew Marshall and Anne Kellerman of Florida State University; MagLab chemist Huan Chen; graduate research assistant Jonathan Putman; and postdoctoral associate Naween Anand.

Useful to a point, the athlete/scientist analogy breaks down when you get to the trophies. The Superbowl and Stanley Cup are won by teams. Nobel Prizes and Copley Medals are awarded to individuals.

"In sports you're rewarded if your team wins," said Brasier. "Those reward structures are not quite so apparent in the academic world." That's one of the problems scholars in the field of science teamwork are trying to change.

If early-career scientists like Jonathan Putman (pictured above) are any measure, they may already be seeing results. Putman played soccer, tennis, and baseball, which seems to have influenced his approach to science. In his experience as a grad student in chemistry, he's frequently seen fellow researchers take one for the team, in the name of science.

"There are often times in these collaborations and meetings when you're bouncing ideas off of each other," Putman said, "and someone else may come up with a great idea that results in a publication for you. They don't often care if they’re on it; they just want to see the field progress."

Promote Team Science!

You can help promote team science by clicking below to print out four team-themed posters to pin up at your home, school or lab.

Story by Kristen Coyne. Photos by Dave Barfield.