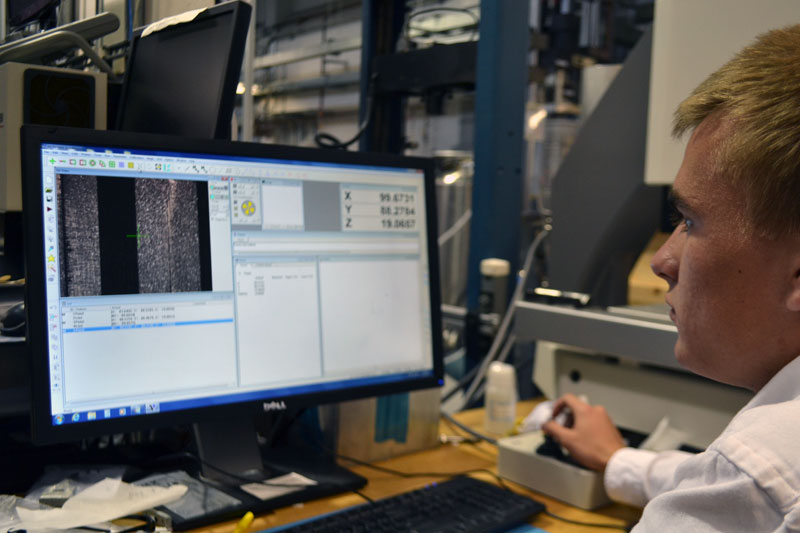

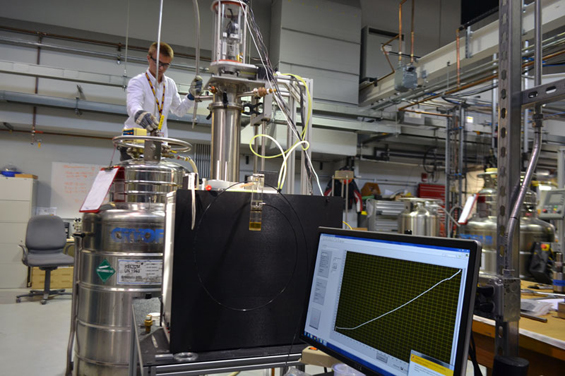

Kyle Buchholz strolls into the Mechanical and Physical Properties Lab at the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory like he owns the place. With a casual confidence, he sets to work testing how much the size of a sample of fiberglass will change as its temperature changes. Moving from an inspection microscope to a device called a dilatometer to tanks holding frigid liquid helium, he flows through a precise sequence of steps like he really knows what he's doing.

He doesn't.

In all fairness, you can't reasonably expect Kyle, a 17-year-old senior at Leon High School in Tallahassee, Fla., to be an expert on this process — let alone on the science and engineering behind it. After all, he is only two months into a Internship Program"student internship at the National MagLab. But that doesn't mean he can't roll up his sleeves and dive right in.

"I think it's a better way to learn it," says Kyle's mentor, MagLab mechanical engineer Bob Walsh. "If you explain every step of the details, you kind of overwhelm him."

The fact that Kyle doesn't exactly know what he's doing, or why he's doing it, doesn't worry Walsh.

"We just make him do stuff," he explains curtly. "It will sink in eventually. Just do it."

A different type of learning

The MagLab's internship program, offered through its Center for Integrating Research & Learning, has been providing hands-on opportunities to area high school students for years. Under the guidance of mentors, students spend a few afternoons a week on projects that expose them to science in a way, and in an environment, very different from their classrooms.

The internship is great fit for Kyle. He has known since second grade that his future is in science and engineering — "I like definite answers, not ones you have to argue," he says. And having helped his dad with numerous building projects over the years, he's handy with tools.

In Walsh's lab, Kyle has plenty of tools to work with. His job consists of taking samples of fiberglass, freezing them to -456 degrees Fahrenheit (-271 degrees Celsius), then measuring how much they expand as they warm up to room temperature.

This approach to learning science compliments what he does in his second period physics class. It's also quite different. In class, Kyle explains, they learn laws and formulas as they operate in a "perfect world." In Walsh's lab, he says, "We're testing actual things."

In his high school physics labs, it's okay if results are a little off. "What matters is that you grasp the concept," Kyle says. In Walsh's lab, however, the goal is accurate results. The facts and concepts behind those results will reach Kyle's brain gradually — but through his hands rather than a textbook.

"There are certain scientific concepts I don't get yet," says Kyle. "As long as I get the results, I'm fine."

Spoon-feeding, this ain't.

Although both teaching approaches end at the same body of knowledge, they start at different points. Before coming to the MagLab, for example, Kyle understood the definition of thermal expansion from class: "I knew things expand when they're hot and they contract when they're cold."

But by measuring this phenomenon with his own hands, Kyle can add a new layer to that knowledge that makes it more meaningful, nuanced and memorable: Metals resist expansion and contraction more than polymers.

Not that Walsh spelled any of this out for him.

"He gets me to arrive at my own conclusions," says Kyle. "He's getting me more independent, I guess. It's a lot of trust. The fact that he trusts me, it's pretty cool."

Small role, giant project

Another thing that is cool about Kyle's internship: It's for-real work on a for-real project.

As one of the best labs of its kind, the Mechanical and Physical Properties Lab tests materials involved in important projects across the globe — including the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER), a massive experimental fusion reactor under construction in France. Walsh's lab is the primary materials research and qualification lab supporting the U.S. portion of this global effort.

The giant ITER reactor, which will feature more than 20 superconducting magnets, is the core of a huge scientific experiment intended to prove the viability of fusion as an energy source. It involves billions of dollars, decades of time and thousands of individuals.

Bob Walsh is one of them. So, now, is Kyle Buchholz.

By testing the properties of different fiberglass samples, they are helping identify the exact type of fiberglass best suited for insulating the ITER superconducting magnets, which will be assembled into a central solenoid towering some 60 feet (18 meters) tall. Project scientists will need to know precisely how much the fiberglass will expand and contract in the superconducting magnets, which operate at extremely low temperatures.

Kyle will probably be well into his career (he is still deciding between physics and mechanical engineering) before the ITER project is completed. But when it is, he will remember the small role he played.

"It's kind of cool that I can trace something [from ITER] to me," he said.

For Walsh, who has been reaping professional recognition for decades, the cool part is helping smart scientists-in-the-making like Kyle. A serial mentor, he has taken more than a dozen students from middle school to college under his wing during his MagLab career, as well as coaching local robotics clubs and sports teams.

Why mentor so much?

When his students are busy preparing presentations at the end of their projects, Walsh sometimes questions whether they really understood what they were doing. Then, in front of peers, parents and teachers, they nail it, showing and telling all that they learned at the MagLab. That's Walsh's payback.

"You just realize, holy cow, they got that," says Walsh. "They just explained that perfectly."