What did scientists discover?

Electrons in metals behave like chaotic bumper cars, crashing into each other with great frequency. While they may be reckless drivers, this new result demonstrates that this chaos has a limit established by the laws of quantum mechanics.

Why is this important?

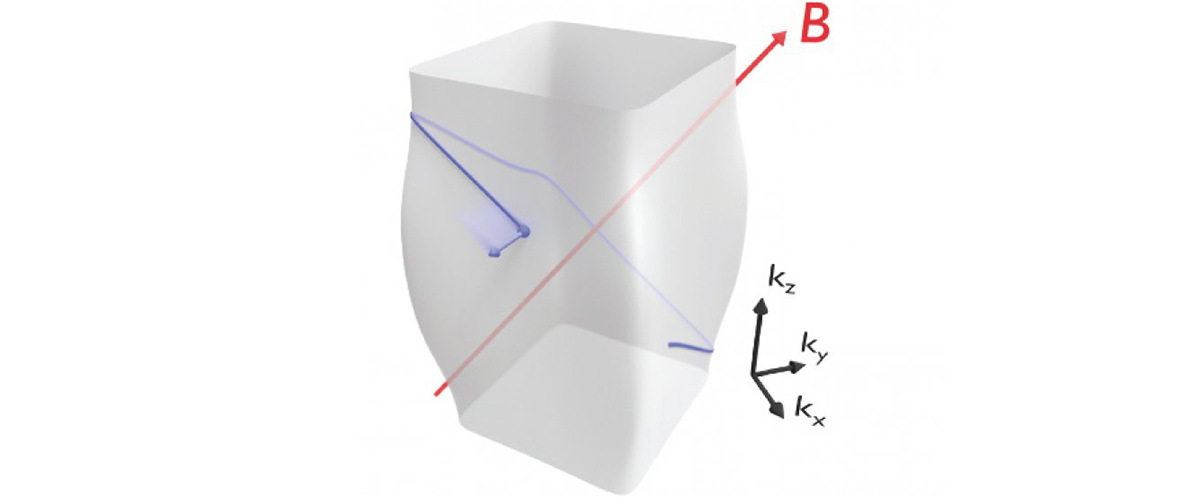

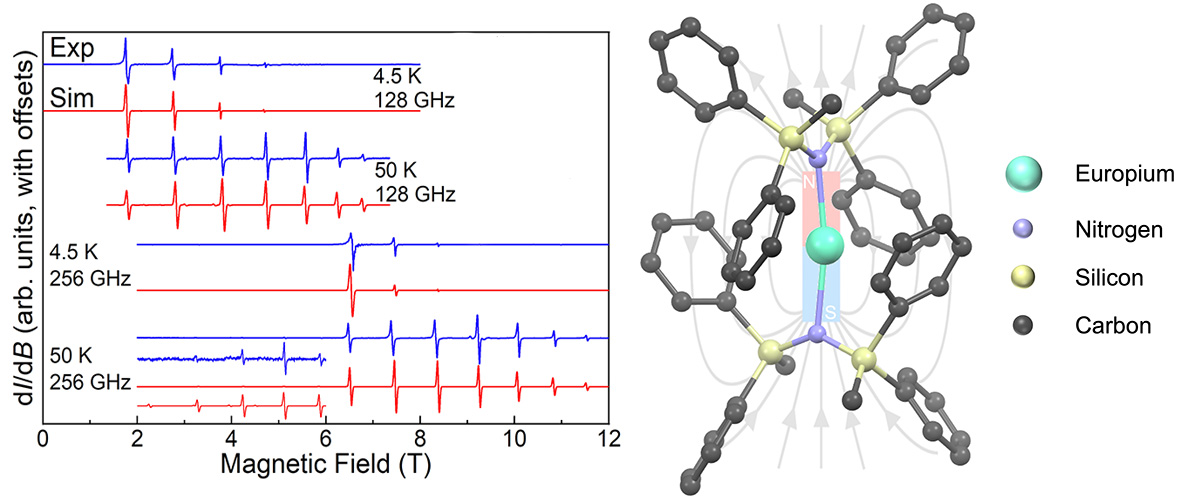

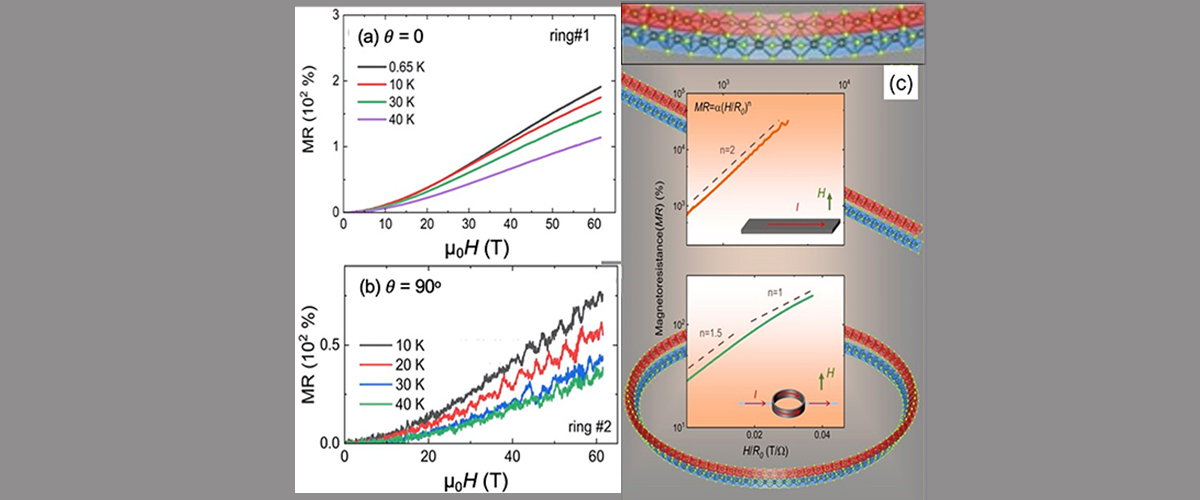

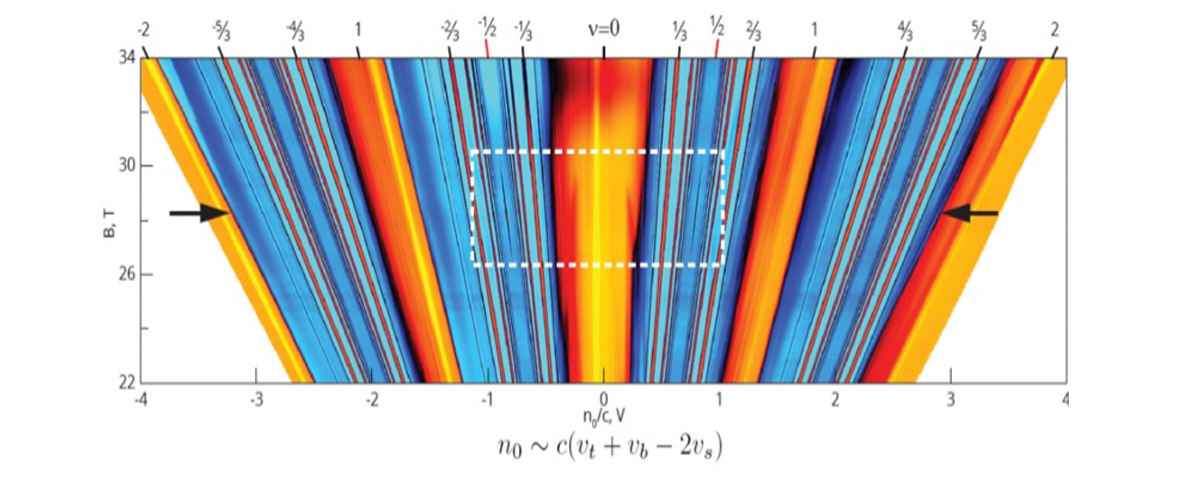

MagLab users studied the strange metal phase of a high-temperature superconductor. Superconductivity has the potential to revolutionize the way we carry and store energy, but we still do not understand the workings of the most promising materials for this technology, a fact that delays their applications. The strange metal phase is just one facet of these superconductors, but a facet that plays a key role showing up at a quantum phase transition close to where superconductivity is the strongest. High magnetic fields revealed that the strangeness of these metals is dictated by a limit of physics so far unexplained: the Planckian bound. The Planckian bound limits how often electrons can collide with each other in a metal. Because limits in physics are the guardrails of new concepts, this discovery of the role of the Planckian bound is research that has been stalled for decades.

Who did the research?

G. Grissonnanche1,2, Y. Fang2, A. Legros1,3, S. Verret1, F. Laliberté1, C. Collignon1, J. Zhou4, D. Graf5, P. A. Goddard6, Louis Taillefer1,7 & B. J. Ramshaw2,7

1Université de Sherbrooke; 2Cornell University; 3Université Paris-Saclay; 4University of Texas at Austin; 5National High Magnetic Field Laboratory; 6University of Warwick; 7Canadian Institute for Advanced Research

Why did they need the MagLab?

The 45T hybrid magnet – and the ability to stay at 45T for many hours at a time - was essential to suppress the superconducting state and measure the electron collision rates for many magnetic field orientations and temperatures.

Details for scientists

- View or download the expert-level Science Highlight, Linear-in temperature resistivity from isotropic Planckian scattering rate

- Read the full-length publication, Linear-in temperature resistivity from an isotropic Planckian scattering rate, in Nature.

Funding

This research was funded by the following grants: G.S. Boebinger (NSF DMR-1644779); B.J. Ramshaw (NSF DMR-1752784); J.-S. Zhu (MRSEC DMR-1720595

For more information, please contact Tim Murphy.