Contact: Ali Bangura

TALLAHASSEE, Fla. — Scientists working at the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory have discovered "double superconductivity," a surprise finding that could provide new insight into how certain materials carry electricity without resistance, possibly opening avenues for quantum computing and other applications.

"This is quite unprecedented," said Shafayat Hossain, first author of a paper on the discovery published in Nature Physics. "We don't yet have a clear understanding of what's going on here."

Superconductivity was first discovered more than a century ago in certain materials cooled to liquid helium temperatures below -450°F. Electrons move through the materials without scattering, losing no energy and producing no heat. In the 1980’s, scientists developed a new class of superconductors that work at about -300°F. Researchers are still seeking to fully understand how these superconductors function and pursuing a superconductor that works at room temperature.

Hossain's research team included physicists at Princeton, Beijing Institute of Technology, the University of Zurich and the MagLab. They measured double superconductivity in the material cesium vanadium antimonide (CsV3Sb5).

"There seems to be an additional superconducting state developing within an existing superconducting state," said Hossain, noting this phenomenon has never been seen before in any material. "They are all located in the same physical plane, the same lattice."

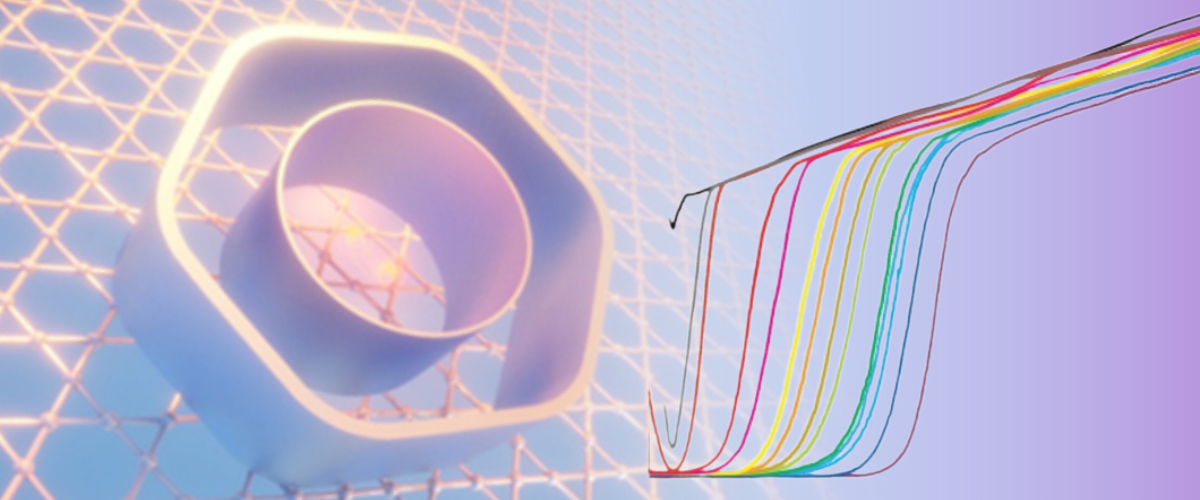

That lattice is called kagome, a hexagon pattern of corner-sharing triangles named after the traditional Japanese weave of the same structure. At the MagLab, the team scrutinized a thin CsV3Sb5 kagome crystal at extremely low temperatures, taking ultra-sensitive measurements of electrical resistance, thermal conductivity, and heat capacity.

As they cooled the material below -453°F, the lattice began carrying electricity without resistance. In such a superconducting state, negatively charged electrons, which normally repel each other, form pairs to move through the material without scattering, like dance partners tangoing through a crowd.

As the material cooled a degree or so lower, the unexpected happened. A second distinct superconducting phase emerged.

Though researchers aren't sure of the cause, they believe some electrons fail to pair in the initial superconducting phase. Those remaining electrons then couple and begin to superconduct when the material gets even colder. Hossain says the two groups of paired electrons seem to act independently, as if they are each dancing to their own tune.

"Something different happens from the first superconducting state. These two pockets pair up in a different way. So electrons in one pocket pair in one way, electrons in another pocket pair in a different way," said Hossain. "One pocket does not really care about the other pocket’s existence. They don't talk to each other."

The two states of superconductivity also show directional preference. Think of those dance pairs again— one group is dancing toward the front of the room, the other toward the side.

While all this unconventional electron movement is happening, the material displays yet another peculiar characteristic — signs of its own intrinsic magnetism.

"Since ferromagnetism and superconductivity usually do not coexist, one cannot but wonder how unusual this state is," said Luis Balicas, Florida State University physics professor, MagLab Research Faculty and a senior author on the paper, "Several of our measurements reveal surprising behavior."

Understanding this surprising behavior could inspire new technologies for energy-efficient electronics, quantum sensors, quantum memory, and future computing platforms. The group is planning more study.

"This is still ongoing work. Very interesting and complicated," said Hossain. "Who knows what groundbreaking superconductor in this category will be found next? We are always on the lookout because these materials often reveal unexpected quantum states."

The MagLab provides the unique tools needed to continue this exploration of the quantum universe—with the strongest magnetic fields in the world, extremely cold environments, precise instrumentation, and expert staff.

"It's both the personnel expertise, the technical expertise and the instrumentation capabilities that are very well satisfied at the MagLab," said Hossain.