Contact: Kristin Roberts

TALLAHASSEE — The simple gray squiggle produced 50 years ago this month may not look like much. But the line launched an entirely new research technique and set a trajectory that the MagLab's Alan Marshall is still following to this day.

The line was the first mass spectrum made using Fourier-Transform Ion Cyclotron Resonance, FT-ICR for short.

Marshall and fellow professor Mel Comisarow produced the groundbreaking spectrum on December 17, 1973 at the University of British Columbia. They took Fourier Transforms, a mathematical tool for converting signals over time into a spectrum of usable data, and applied the tool to ICR.

"I knew about Fourier Transforms from NMR (nuclear magnetic resonance) and thought maybe we should try that for this other experiment," explained Marshall, who is chief scientist of the MagLab's ICR program and Robert O. Lawton professor of chemistry at Florida State University.

"Most people think new ideas come out of the blue. A lot of developments, people take something well known in one field and move it into a different one. That's what I did."

- Alan Marshall

What he did would revolutionize analytical chemistry by dramatically increasing speed and resolving power of ICR while also generating a mass spectrum of many molecules at once, rather than one at a time.

But, at the time, few scientists seemed to appreciate the invention. The prestigious International Journal of Mass Spectrometry actually rejected the pair's initial paper.

"The first spectrum was one peak, so people weren't too excited about that. It actually took a while to catch on," Marshall said, looking back.

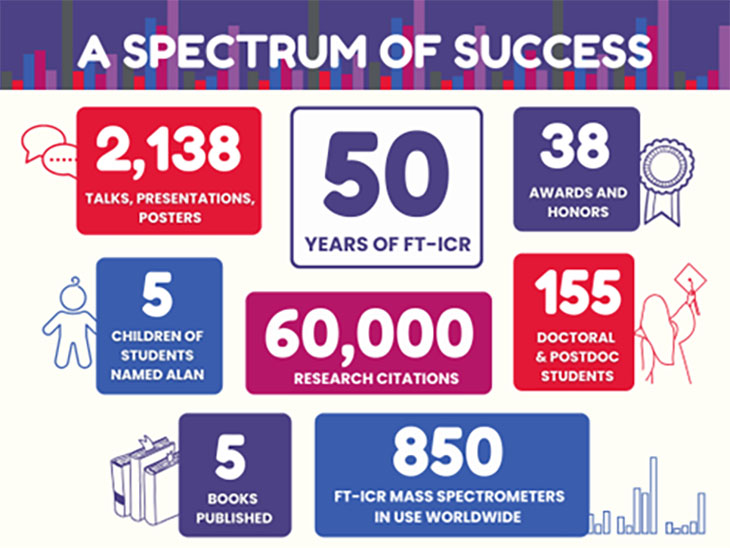

Eventually, catch on it did. The first commercial FT-ICR system was developed by the end of the '70's. Now 50 years after its invention, Marshall says more than 850 FT-ICR mass spectrometers are in use, everywhere from academic institutions to oil companies to the pharmaceutical industry.

Alan Marshall and Fourier Transform Ion Cyclotron Resonance, by the numbers.

Image credit: Caroline McNiel

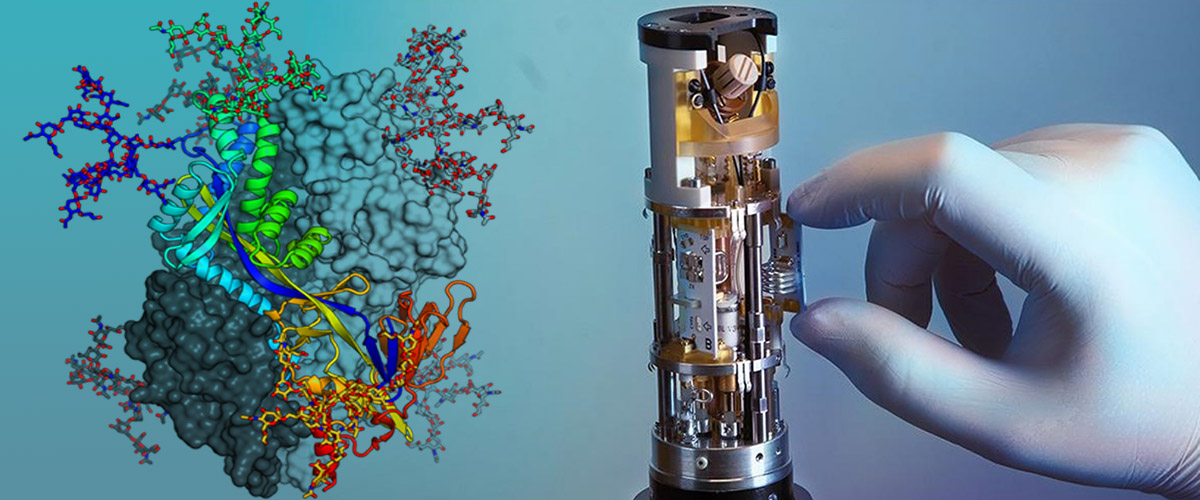

Nowhere is the technique more powerful and precise than at the National MagLab, which Marshall joined when it opened in Tallahassee. As the lab's first ICR director, he built a program that sets records for magnetic field strength, mass accuracy, and resolution and offers these state-of-the-art tools to users from around the globe. Since its origin, the FT-ICR Facility has hosted more than 3,300 users resulting in more than 720 peer-reviewed publications.

"People come here as much for the expertise as they do for the toys. Because we have some of the broadest and deepest knowledge of the technique anywhere," he said.

The MagLab's 21 tesla FT-ICR system, the most powerful mass spectrometer in the world.

Image credit: Stephen Bilenky

MagLab's FT-ICR is best known for helping to create the field of petroleomics — detailed chemical fingerprinting of petroleum, one of the most complex liquids on earth.

"We can identify oil spills, tell who did it and what's in it," said Marshall.

MagLab scientists also utilize FT-ICR to track forever chemicals and carcinogens in our soil and water, are analyzing samples from the Maui wildfires, and are working to develop new sustainable jet fuel by harnessing agricultural waste from corn harvest.

"The guy is just crazy smart. He can see things other people cannot see. He connects areas other people can’t connect," said Ryan Rodgers, a MagLab faculty researcher who was Marshall's student and has worked with him for 28 years.

Rodgers says in addition to Marshall's "sublime" intelligence, he shows incredible confidence in the people he works with.

"It can be done. Let's go do it. Make it happen," is the mantra, according to Rodgers.

Work with one of his last graduate students - FSU graduate research assistant Joseph Frye-Jones - has taken the FT-ICR technique out of this world as they are analyzing and cataloguing organic matter in meteorites and lunar soil.

"The two main things that have guided me," Marshall said, "Have broad scientific interest, because you never know where the next idea is coming from. And collaboration. I expect all the students and postdocs to work with outside users, because I figure it broadens their outlook. Maybe they make a friend, maybe that person writes a letter, maybe they hire them."

He also leads by example, coming to work seven days a week his entire career.

"On the weekends, I can do what I like. During the week I have to do chores as well," Marshall explained with a smile. "I tell my students they have to be interested in what they're doing. They won't do well unless they're interested."

The hard work and passion have garnered dozens of honors and awards. Marshall is a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences and was inducted into the Florida Inventors Hall of Fame. His research has been cited an astounding 60,000 times.

"That's one of my proudest accomplishments, I think. Because it shows other people are using the technique and value it," he said.

MagLab and the FSU Chemistry Department recently celebrated the FT-ICR anniversary with a symposium featuring Marshall along with colleagues and collaborators, including many former students.

Alan Marshall at a symposium held Nov. 3, 2023, marking the 50th anniversary of the invention of FT-ICR.

Image credit: FSU College of Arts & Sciences

The 79-year-old is now finally looking to slow down. He is set to retire in the spring of 2024 and plans to spend more time with his two children and four grandchildren. But not before pausing to celebrate his invention five decades ago, the remarkable work he's done since then, and the impact left for generations to come.

"The students are the big joy. Watching them come along has been a real treat," Marshall says of the 155 PhDs and postdocs he has mentored, noting that five of them even named their sons after him.

"I still keep in touch. It's fun to see them succeed," he said, "It's like family."

"It's a fantastic legacy," Rodgers said.