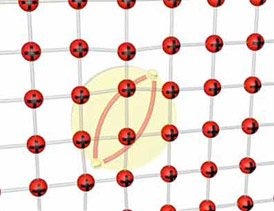

Pairs of electrons, called "Cooper pairs," don't scatter in superconductivity.

Superconductivity is magic! It's frictionless electricity. You may say, "Well, in everyday life we pass electricity through copper wires and it doesn't seem to show much heat." But it does. Because the electrons are negative, and the metal ions are positive, they're attracted towards each other, so occasionally they collide with each other. And when they collide they create friction, they produce heat. Now you might say, "Negative charges should repel each other, negative and positive charges attract each other."

The miracle and the magic of superconductivity is that if you cool them to a sufficiently low temperature, then you enter a state where the two negatively charged electrons are attracted towards each other. Now we have pairs of electrons that don't scatter, and we can pass very large currents without any friction.

This interaction that causes superconductivity only operates up to a maximum temperature of about -300 degrees Fahrenheit. My interest is in understanding how to make materials that are good superconductors: operating up to the highest possible temperatures, also operating up to the very highest magnetic fields, and that can be fabricated in useful forms so that we can make things out of them.

What could we do if we had these things? We would, in fact, start to replace copper wiring. Perhaps 30 percent of the energy generated in the United States is wasted. And this would be one of the one ways in which even more complex materials could pay for themselves.